Does Water Unite or Divide Us?

Posted on: September 2016Tom Veitch, Global Action Plan

Tom Veitch, Global Action Plan

|

Tom Veitch has a wide experience of delivering environmental programmes in a community context, including nearly 8 years at Global Action Plan and three years with a faith-based community programme in Merseyside. His background is in the water industry with 7 years at United Utilities. Tom developed many of GAPs' interactive activities on water and energy and loves using them to help people see how they can save energy and water. He was project manager for the PlugIn Hay Mills project. |

Water may just be H2O, but that doesn’t mean that we all see it the same way. There are clear differences between groups of people in how they view and use water. This was well demonstrated recently by Faith in Water, a Thames Water, London Sustainability Exchange (LSx) and UCL study, which explored attitudes, beliefs and practices around water use with seven different faith communities in London, the outcomes of which have recently been published as a Toolkit

Differences can relate to specific religious practices, such as the need for ritual washing in some faiths, as well as those which are more cultural, such as standards of cleanliness. This may be as simple as whether it is considered necessary to rinse washing up to remove traces of detergent or how clean the water when washing vegetables. The Faith in Water report concluded that

“Almost universally, cultural practices of water use were more commonly mentioned than religious observances.†Faith and Water Toolkit (section 4.2)

In a similar way, studies have shown a wide range of approaches to washing up in the UK and across Europe, with a corresponding variance in the amount of water used. Participants in the UK study used between 14 and 206 litres of water to wash the same 12 standard place settings.

Over the past 20 years a number of initiatives and studies have explored the link between faith, culture and water, with contributions from organisations such as Waterwise, CIWEM, Alliance of Religions and Conservations and LSx . From this we now have a good evidence base for ways that are appropriate to engage with different cultural audiences, which reveals some interesting distinctions, for example:

“We had run a lecture series with the Muslim community which went really well […] when we ran a lecture series with the Hindu elders in one of the temples, they seemed not really interested because they didn’t want somebody external lecturing them, that wasn’t their usual style. What they would do is run more of a debating society around the scripture. If I had done it again, I would have sourced a respected Hindu spiritual leader and picked up on a particular theological aspect of the scriptures, creating more of a debating society.†(Gayle Burgess, Behaviour Change Programme Director)

The importance of responding to the specific needs of the audience was echoed in the Faith and Water Toolkit (section 3.4), which identified that, “religious and everyday practices can be significantly different for Muslim communities of Asian or African origin.â€

Awareness of differences is important, as it helps us avoid making incorrect assumptions about how people may view or use water. However, there are other times when it is important to focus on what we have in common – for example when delivering area-based projects in a mixed community. Emphasising differences, even when it is done with the best of intentions, can be counterproductive. An episode of the BBC Radio 4 “Human Zoo†programme made a clear case for why we need to be very careful how we talk about “the otherâ€.

"If you point out even trivial differences you reinforce people’s sense of being different. The way to overcome racial animosity […] is to preach common and group identities [...] saying that we’re all in the same team.â€

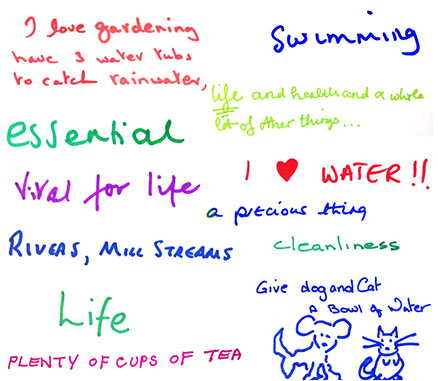

In a recent project in Birmingham, supported by the Environment Agency, Severn Trent Water and Arup, Global Action Plan worked with a small multi-cultural community to bring people together to celebrate and save water. We asked residents what they valued about water and reflected this back to other community members through events, social media and in printed materials. In effect we were saying, “this is what other people like you (in your area) value about waterâ€.

We did this in a very simple way, using printed postcards and coloured markers and digitising the contributions. The results identified more commonality than difference, with people talking about enjoying water at parks or swimming pools or seeing water as:

• Essential

• Vital for life

• A precious thing

In this context of shared values, the differences appeared more subtle

“Hospitality is very important in Afghan culture. If I cannot offer a drink of water, then I am not a good host."

“Water is used by Christians for baptism – signalling and new start and welcoming people into a community.â€

Why does this all matter?

How we talk about water, and whether we make distinctions between people, will impact on how customers receive the information. When we want to speak to a specific audience, such as those belonging to a particular faith community there is now a rich and growing body of evidence that can help identify trusted messengers, key messages and links to religious texts, traditions or practices.

When talking to individuals this knowledge can help us to be more sensitive, to understand that they may have a different view on what is important to them when they wash up, or how they shower.

However, when our audience is mixed, and particularly in the light of the Brexit vote that has highlighted deep divisions within our communities, it will be much more productive to look for what we have in common. By doing this we can emphasise common values and make a case for why water is important to everyone and that we can all help to celebrate and save it.