Equitable water access: leaving no one behind, wherever.

Posted on: April 2019Kemi Adeyeye, WATEF network

Equitable water access: leaving no one behind, wherever.

| About the author: Dr Kemi Adeyeye is the Water Efficiency Network Lead and Senior Lecturer at the Department for Architecture and Civil Engineering at the University of Bath |

|

|

This year’s World Water Day was on the 22nd of March, a day when we all consider the importance of water to life, health, livelihood and wellbeing. It is also a time to pause and think about the 2.1 billion people who still lack access to safely managed drinking water services and the 4.5 billion people who lack safely managed sanitation services.

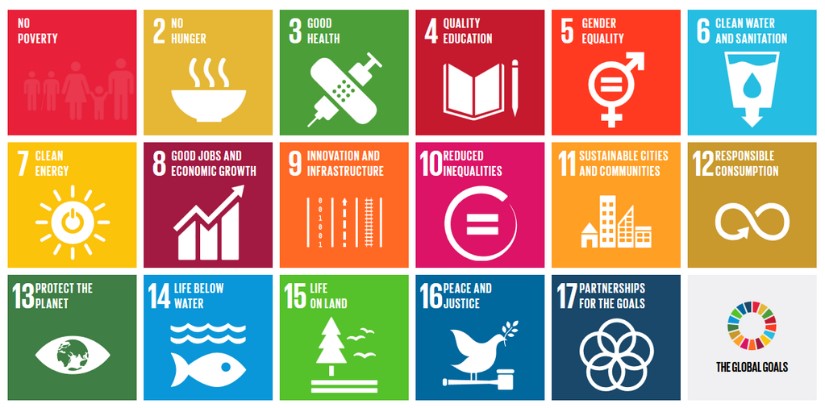

This year’s UN-Water’s theme was “Leaving no one behind: Whoever you are, wherever you areâ€. It recognises the disproportionality of water access that still exists based on location, race, gender, age, ability, cultural or economic status etc. It also brings the equitability of water access to the forefront of the water discourse. More so, as basic water and sanitation access (SDG 6) has direct or indirect impact on access to education (SDG 4 - especially for girls), good health (SDG 3), reduced poverty (SDG 1 - due to access to food and to maintain productivity and livelihoods). It can also promote or affect peace and justice (SDG 16) and reduce inequalities (SDG 10). Especially inequalities due to household status – women and girls, those based on cultural status and social castes, and those (the focus of this blog) based on location – urban versus rural etc.

It is estimated that more than half of the global population live in towns and cities, and this could rise to two-thirds by 2050. Rural-urban migration is a key factor, with the urban population estimated to grow from 3.9 billion people today to 6.3 billion in 2050. This raises two challenges:

- Providing adequate water and sanitation to urban areas in line with the significant population increase

- Maintaining basic levels of service to informal settlements, peri-urban and rural areas

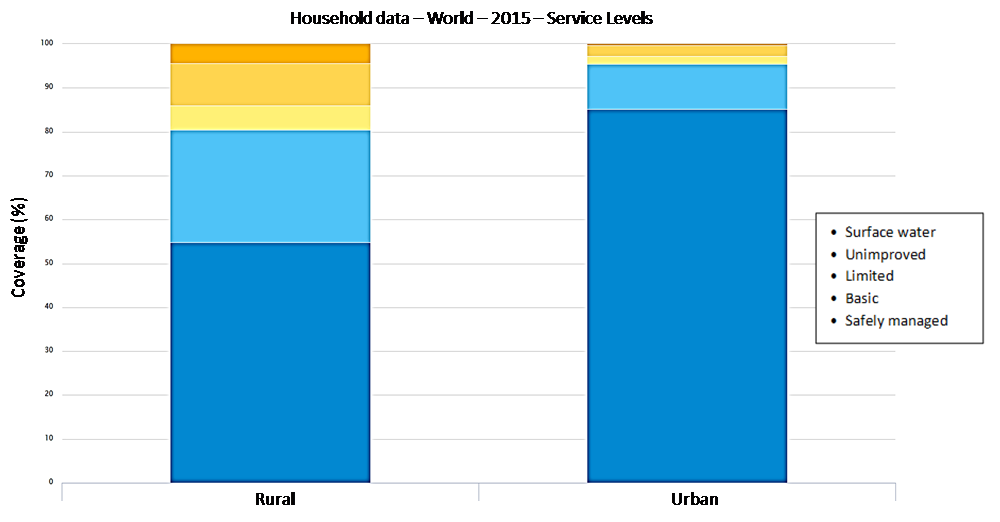

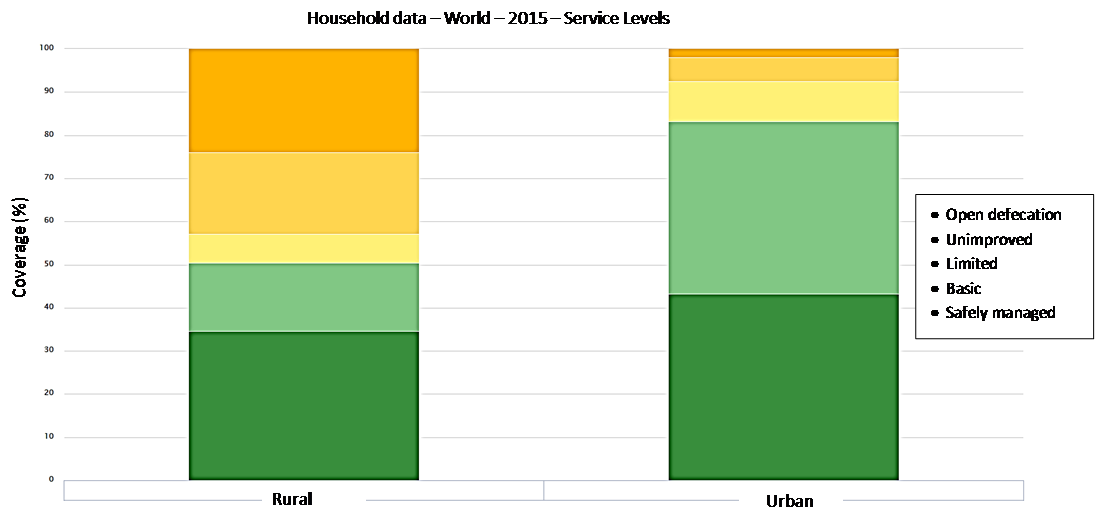

Globally, 2 out of 5 people in rural areas use piped water supplies compared to 4 out of 5 in urban areas (WHO/UNICEF 2017) and 80% of those that lack access to potable water live in rural areas (World Bank data). In sub-Saharan Africa, almost 20% of rural dwellers had to walk at least 30 min to collect their water compared to only 7% of urban dwellers (WHO/UNICEF 2017 - Figures 2a and 2b). Geo-political instability, wealth disparity and poor/unmanaged planning also add issues of informal settlements and urban sprawl, inadequate and poorly maintained water and sanitation infrastructure, and negative social issues like crime and vandalism to the mix.

Although, resources (land, water etc.) are typically more abundant in rural areas, the proportion of the population using an improved water source remains substantially lower in rural than urban areas. Rural water quality is also often comparatively worse. So, a rural-urban bias may inadvertently occur due to (Bain et al. 2014):

- Increasing population of urban areas

- Unregulated, unmanaged resource abstraction

- Indiscriminate land development – typically housing

- Social and economic inequity between urban areas and peri-urban areas or slums

- Liveability and economic classes are difficult to compare between urban and rural areas

- The cost of infrastructure provision per population in rural areas are higher

Figure 2a: Rural and urban service levels for drinking water (2015) Washdata.org. Note: some country data missing.

Figure 2b: Rural and urban service levels for sanitation

(2015). Washdata.org. Note: some country

data missing.

“Leaving no one behind†therefore needs all of us: academics, policy makers, practitioners and NGOs to apply our collective efforts to make sure that we achieve water access for the few, as well as the many. Even if it is spatially, financially and economically challenging. According to the World Economic Forum, improving poor water access has economic costs but also offers dividends. They estimate that almost $18.5 billion in benefits can be achieved through universal access to basic water and sanitation meanwhile $260 billion is lost globally each year from the lack of basic water and sanitation. There is also a $4 return from lower health costs, higher productivity, and fewer preventable deaths for every $1 invested in water and sanitation.

In 2017, the Joint Monitoring Program convened an expert taskforce on inequalities. The taskforce was asked to prioritise: informal urban settlements, disadvantaged groups, affordability of WASH services and intra-household inequalities (such as gender and disabilities). Following the launch of the 2019 World Water Development Report (WWDR) ‘Leaving No One Behind’, other world organisations like WHO, UNICEF and UNESCO are also prioritising the issue. In the UK, research grant funders, institutes and organisations also recognise the importance of further efforts in this area. The Royal Academy of Engineering’s Industry Academia Partnership Programme of 17/18 (ref: IAPP1R2/100196) funded the University of Bath, CSIR Pretoria and the University of Venda’s project on resilient water infrastructure. In addition to providing training, the project also investigated issues of water security and access and found that urban-rural dichotomies can impact on equitable water access. We also found that water challenges and priorities for municipality and rural communities were, unsurprisingly, different. Water access – equitable, accessible and affordable for the rural communities; finance for water infrastructure and secure water sources were the priority of municipalities. This study only just concluded so we will be able to report and publish full findings shortly.

In conclusion, the world is making positive strides towards universal water access for all. However, special attention is still needed in areas where unequitable water access remains a challenge to health, well-being, livelihoods and productivity. Collective efforts are needed to ensure that governance, research, technology, social and economic solutions are positively applied to ensure that no-one is truly left behind.

Figure 3: Example of urban/peri-urban areas explored in the RAENG study. The image on the right shows an example of a water access point used by nearby villages kilometres away.

References:

- WHO/UNICEF (2017), Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene: Update and SDG baselines.

- Bain, R. E., Wright, J. A., Christenson, E., & Bartram, J. K. (2014). Rural: urban inequalities in post 2015 targets and indicators for drinking-water. Science of the Total Environment, 490, 509-513.